In the midst of concrete monsters

This water now reflects the sky

It is nature that fights

This neighborhood is less dark

In the midst of concrete monsters

The lake is a dream come true

It is nature that resists

Rome is less dark tonight

The opening title of this short paper is taken from the hip hop group Assalti frontali and the rock band Il Muro del Canto’s song “ll lago che combatte (The lake that fights)”, which was released in 2014 and formed part of the activist and community movement to save the Lago Ex SNIA, a lake in the Pigneto-Prenestino neighbourhood of Rome. I came upon this special lake through my colleague at the University of the West of England, (UWE) Professor Ioannis (Yannis) Ieropoulos.

Yannis and I share an interest in restorative, reparative and healing futures. A specialist in self-sustainable systems, he directs the Bristol BioEnergy Centre at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, UWE, where he works with his team on waste utilisation and energy autonomy with a focus on microbial fuel cell (MFC) and bio-electrochemical systems (BES). Currently the group is part of the team that leads an EU COST Action project called PHOENIX, which looks at how bio-electrochemical systems (BES) can support the protection, reliance and rehabilitation of damaged environments.

For those unfamiliar with this area, MFC and BESs are devices that convert chemical energy into electrical energy (and vice-versa) by using the action of microorganisms, such as bacteria as catalysts. BESs are very good at converting so-called waste materials (e.g. urine) into energy (electricity) and can also be designed to recover nutrients, metals or remove recalcitrant compounds. Compared to conventional fuel cells, which use a number of substances like potassium hydroxide, salt carbonates, and phosphoric acid, platinum powder and nickel, BESs do not use expensive precious metals or inorganic compounds as catalysts and therefore are not just more environmentally “friendly”, but can also be used in processes of environmental remediation and repair.

In relation to this collection’s focus on “Landscapes of Care”, the PHOENIX project connects to our thinking in that we view microorganisms as part of a broader care network, whose abilities in collaboration with humans play an important role in the maintenance of particular complex and situated urban entanglements.

This idea of the microorganism as a care partner also extends, as noted in the opening interview with Soft Agency, María Puig de la Bellacasa’s notion of the human as a caretaker by expanding this relation to include non-human others, whose work also forms part of an intentional network of landscape recuperation. Thinking through this logic, I suggested that we speak to Yannis about his work, which led to an introduction to his colleague and co-chair on the PHOENIX project, Dr. Andrea Pietrelli. Andrea is also an MFCs expert, who studied at the Sapienza University in Rome.

The Sapienza campus is a stone’s throw from the neighbourhood of Pigneto-Prenestino, which lies in south-east Rome. Situated outside of Rome’s formal walls, historically the area takes its name for the pinewoods (Pigneto) that lined the private villas and farmlands that made up the neighbourhood. Aerial views of Pigneto-Prenestino demarcate its distinctive triangle-shaped perimeter, which is bounded by the ancient roads Via Prenestina, Via Casilina, and Via dell’Acqua Bullicante.

The area, which also lies to the east of Rome’s main train terminal, was by the turn of the 19th century home to a large working class and migrant population who found employment in the neighbourhood's multiple factories. Like many other European inner city industrial areas (for example Poble Nou, Barcelona), Pigneto-Prenestino’s boom time was in the 1920s-40s, when the area’s distinctive architectural character, industrial spaces and eclectic mix of buildings was further embellished by the local community's strong socialist and left-leaning, working population. This atmosphere provided the building blocks with its contemporary “vibrant”, “alternative” and “hip” imaginary, but during the 1960s-90s the area fell into a period of neglect and speculation.

Central to the area’s history of urban renewal and speculation is the former chemical and textile SNIA Viscosa factory, which sits at the heart of this urban lake story. In the mid-1920s the Italian rayon industry grew massively with the SNIA Viscosa plant leading the way, becoming one of Italy’s most successful industrial stories. Operating from 1923 until its closure in 1954-55, the factory also used a highly toxic carbon disulfide (CS2) process to manufacture rayon, resulting in the soil and water in the area becoming poisonous. After its closure, the factory and the area were largely left to nature and a rewilding process occurred, which with time has enabled the landscape to heal.

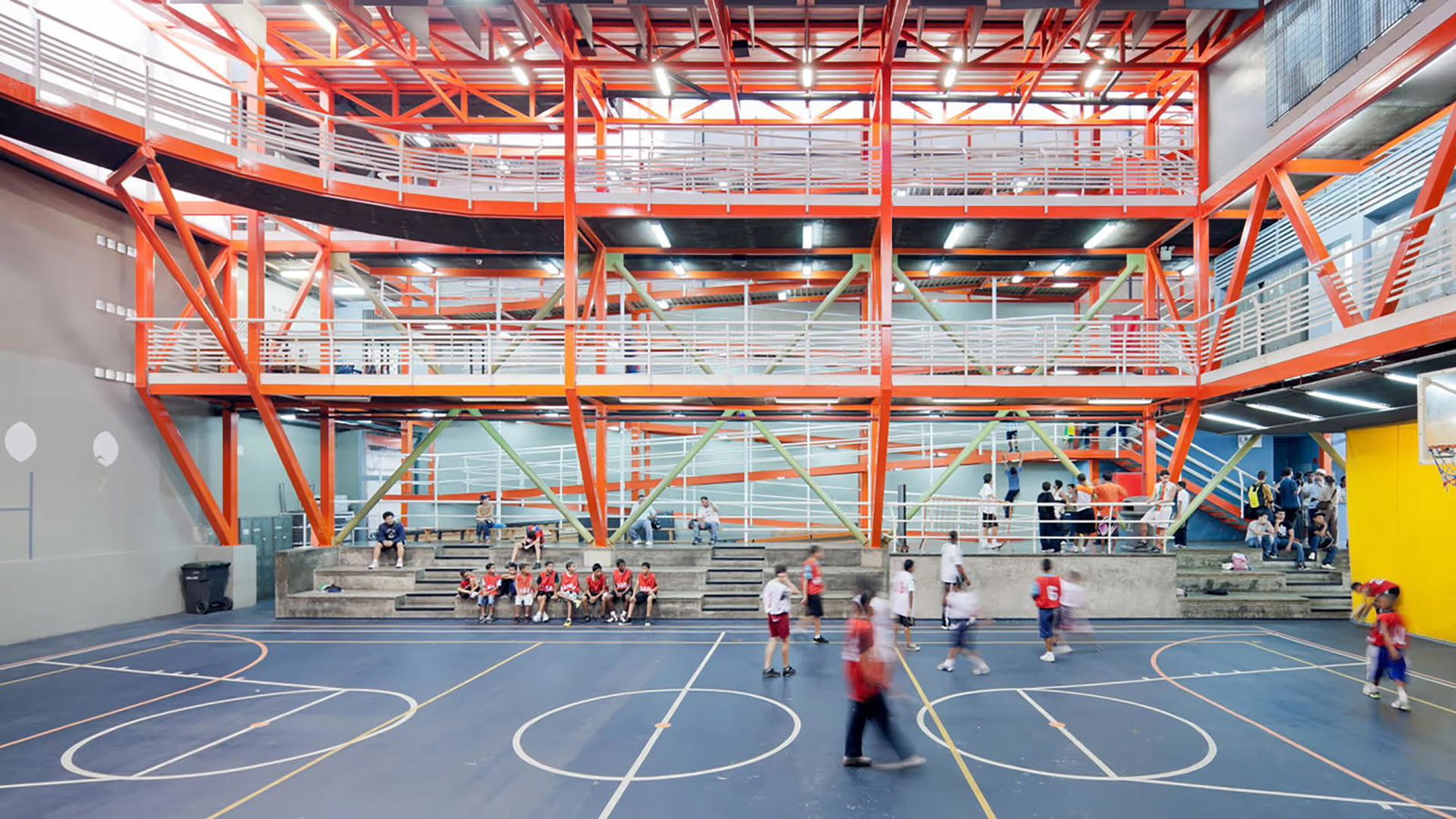

However, in the 1970s, part of the site was sold by the local council to a private property and construction company owned by the tycoon Antonio Pulcini, who in the early 1990s began digging up the site in an attempt to build a shopping centre and car park. During construction the company hit an underground aquifer, resulting in the flooding of the area and the creation of the now infamous lake. Due to the scale of the flooding and as the site had not been properly vetted before works began, construction was considered illegal and halted. As Pulcini and the municipality of Rome wrangled over the site’s zoning and flooding, local people took advantage of this now “wild” urban space, and began to sneak in, using it and the lake more and more. This led the community, along with local activists, to take over an old part of the factory situated outside of Pulcini’s land and form the social and cultural centre Ex-SNIA, which has become a central hub in the fight to democratise the whole area and turn it into a public park. It is from this base at Ex SNIA that local communities along with others continue to work tirelessly to retain the lake and the park as a public good.

Mobilising around this effort, various neighbourhood community groups together with activists, scientists, designers, architects and others, now lobby for the area to be considered as a natural, ecological corridor which is now also home to hundreds of species of wildlife. Drawing upon expertise from Sapienza University as well as others, quantifying the ecological diversity of the site has, alongside extensive archival work, become one of a number of tactics that the activists and the community use to protect the site. Broader alliances with various neighbourhood associations also led to the creation of a city park called Parco delle Energie in 1997, which also houses a local archive about the area’s industrial past. Parco delle Energie is another example of the powerful community activism that is at play in this neighbourhood. The videos embedded below provide an aerial overview of the lake’s context, including its position within the surrounding industrial zone and its spatial relation to the historic factory buildings and abandoned construction work (video 1), plus a summary (in Italian) of the archive work at the Parco delle Energie, including documentation of the failed construction work and the fight for the lake (video 2).

Credit: Marcello Berengo Gardin

As a result of these activities, over the last two decades, the area has become synonymous with the local communities’ struggle against the municipalities dealing with the site and the behaviour of the construction company who keep trying to resume construction work. As noted by architects Marco Gissara, Giulia Barra, Lorenzo Diana and Stefano Gatti, who are members of the collective Dauhaus – a group interested in urban social dynamics and environmental issues and have been working within the neighbourhood since 2013 – over the decades, various committees have always retained and promoted the same message, calling for the preservation of the former factory for its historical value and the preservation of lakes and the area as a green space for the benefit of all.

A key success came in July 2020, when the administrative region of Lazio (one of the twenty in the country) proclaimed the lake and a portion of the site covering approximately 18 acres to be a “natural monument”. However, even with this declaration, the future of the lake remains unclear as it is still situated on privately owned ground, with activists now demanding that the government legally expropriate the land and make it a public territory.

Alongside this the community also needs to continue to find ways through which to protect the site’s ecological diversity and deal with historic pollution. Colleagues in the PHOENIX project are interested in how this can be achieved in a sensitive manner through the use of bio-electrochemical systems (BESs) and their implementation as bio-remediators, bio-sensors, and bio-reactors in urban planning. Working with BESs in this manner could minimise environmental impact, while also supporting local actors and agents with their needs.

Given as noted the factory’s historical use of carbon disulfide, plus other urban pollution issues, the water and soil in the area need to be continually monitored and cleaned. Carbon disulfide has been found to be poisonous, damaging with a range of acute short term to long term physical, neurological and reproductive effects. Writing about histories of toxicity at the site, environmental humanities researcher Miriam Tola, drawing on the work of feminist technoscience scholar Michelle Murphy’s notion of “chemical infrastructure”, describes the site as a “spatial and temporal distribution of chemical agents” which “circulate through systems of production, consumption and waste, producing effects on bodies and landscapes”. While Tola’s work deals with the historical, including memories of past chemical embodiments and workers’ resistance to such toxicities, my colleagues at PHOENIX offer a different cosmopolitical viewpoint in that their work looks to the remediation of such environments through actively co-opting, appropriating and collaborating with microorganisms’ ability to care for and clean the site. As one of the largest European sites of its kind, the lake, as Andrea explained, is an almost perfect example of what can go right and wrong in an urban setting – from industrial success, to failure, to corruption, environmental degradation, community resistance and activism to new found strategies for change and transformation.

For the PHOENIX team there are parallels between the lake and the site of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, where despite the chemical pollution from the industrial infrastructure (a factory or a power plant), nature speaks back to us – asking perhaps for a new form of care in such rewilded spaces that also require new tools and methodologies. The consortium now plans to work with local communities, creating events on site that act as a form of “public school” that illustrates how bio-electrochemical systems tools and technology could help the community to monitor, clean and repair the soil and water via microorganism-centred tech.

Returning then to a more expanded notion of caretaking, this very special urban lake – which based on the communities’ constant activism has been dubbed a “rebel lake” – provides multiple examples of what it means to care for and construct a living cosmopolitical commons practice.

Post Notes

WORKS CITED

1) "IL LAGO CHE COMBATTE" (2014), Assalti frontali & Il Muro del Canto. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dcb_Thrq2P8 extract and translation taken from “The Curious Case of Rome’s Rebel Lake”, Lidija Pisker (2021), Italics Magazine: https://italicsmag.com/2021/04/06/the-curious-case-of-romes-rebel-lake/ (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

2) https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA19123/ (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

3) For a brief summary of the complexities of the sites contested uses and the local communities fight see McKay, J., (2014) “Rome’s rebel lake is a parable of contemporary commons.”: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/romes-rebel-lake-is-parable-of-contemporary-commons/ (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

4) https://dauhaus.org/about-us-2/ (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

5) Gissara, Marco, Barra Giulia, Dina, Lorenzo and Gatti, Stefano. “A Resistant Community, His Lake and His Factory, Rome, The Neighbourhood of Pigneto-Prenestione and The Right to the City.” Contested Cities, Congreso Interncional Madrid, 2016:http://contested-cities.net/working-papers/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2016/07/WPCC-165020-GissaraBarraDianaGatti-ResistentCommunityLakeFactory.pdf (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

6) https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/carbon-disulfide.pdf (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

7) Tola, M. “The Archive and the Lake. Eco-memory, Toxic Labor and the Making of the Commons in Rome, Italy,” Environmental Humanities 11, no. 1 (2019): 194-215. Available at: https://read.dukeupress.edu/environmental-humanities/article/11/1/194/138269/The-Archive-and-the-LakeLabor-Toxicity-and-the (Last accessed July 29, 2021).

8) See for example Piskar, L., (2021) “The Curious Case of Rome’s Rebel Lake”, Italics Magazine: https://italicsmag.com/2021/04/06/the-curious-case-of-romes-rebel-lake/ and McKay, J., (2014) “Rome’s rebel lake is a parable of contemporary commons.”: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/romes-rebel-lake-is-parable-of-contemporary-commons/ (Last accessed July 29, 2021).